Overview

Previously, students will have been introduced to recursively defined functions. I’ve thought a lot about the value of introducing recursive functions at the beginning of algebra II, which can be a discussion all by itself. However, the “Fry Bank Account” problem provides an excellent opportunity for recursive growth functions and the costs of recursively defining functions.

Previously, students will have been introduced to recursively defined functions. I’ve thought a lot about the value of introducing recursive functions at the beginning of algebra II, which can be a discussion all by itself. However, the “Fry Bank Account” problem provides an excellent opportunity for recursive growth functions and the costs of recursively defining functions.

The question is simple: It’s the year 3000 and Fry needs some cash. Luckily, he left $0.93 in a savings account back in the year 2000. If there’s 2.25% interest, how much is Fry’s account worth?

The beauty of how this should play out is that my students won’t have the wealth of exponential knowledge to quickly fall on. I suspect they are unlikely to make the jump right to: Balance = 0.93*(1.0225)^1000. Instead, they’ll have to define it recursively, which leads to some beneficial complications:

b1 = 0.93

bn = 1.0225*bn-1

This should lead to an interesting and meaningful version of Dan Meyer‘s envisioned plan of the clip found by Timon Piccini.

Opener

The opener will give a quick example problem in which students have to recursively define a formula for a geometric sequence. In preparation for Futurama clip, I’ll also ask how much a $59.99 pair of jeans costs if there is 6% sales tax. Here’s a good as any place to note that the the Futurama problem assumes interest compounded annually. This is really not a major concern lesson, but I will be interested to see what kind of questions are asked about how and when the interest rate is applied. I suspect few will see this at first and use the sales tax question as a model to find Fry’s account balance for year 1, year 2, year 3 and so on.

The Main Act

Students will be in groups of three when I play the clip. Before I turn them loose, I’ll steal Dan Meyer’s lead-in questions and ask what types of numbers we think are way too high. What about too low? Otherwise, the only directive I plan to give is “Use what you’ve learned about recursion to find how much money is in Fry’s bank account. As they discuss and come up with ideas, I’ll push when needed: “How much money does Fry have after 1 year? 10 years?” “What is a recursive formula for this instance.”

What I’m really hoping to see is this:

A student feverishly pushing the “Enter” key of their calculator 1000 times. That’s the type of action and situation that really drives mathematics: “There has to be a better way.” Of course, there is. Perhaps some student will write out their work algebraically. Perhaps, then, they’ll see this common factor popping up. However, this would be quite a leap from a concrete situation to an abstract one and I’m not expecting any student to make it. Instead, I want to set the scene for that future abstraction. “Remember when Mark pushed the enter button 1000 times? Wasn’t that awful?” Then we can get to the explicit formula and – whoa – all we need is one push of the button. But for now, I want the focus to be on recursion; what it can do, how we can use it to define methods of problem solving, and why it is not always the best option.

The great part is that even if a student successfully hits the button 1000 times, we can continue the idea of “you’re doing it the hard way” by asking them to graph the sequence. If time permits we can go into the “Sequence” graphing mode on the calculator and start to talk about the shape of the graph: “Does anyone remember from Algebra I what type of graph this represents?” “What does Fry’s bank account have to do with exponential graphs?”

Contingencies

While the goal is modeling growth and decay using recursion, exponential functions is the powerful, underlying concept. Thus, it’s a natural step for a student who breezes through the recursive aspect of the exercise to try to connect an exponential-looking graph to an exponential function. Of course, it doesn’t stop there. We could discuss annual versus monthly compounding interest. Or, as Dan Meyer suggests, to stay on the objective at hand I could ask when Fry hits the $1,000,000,000,000 mark. It’s clips like this that I’m constantly looking to bring into my classroom: lots of roads to take from just a short video of pop culture.

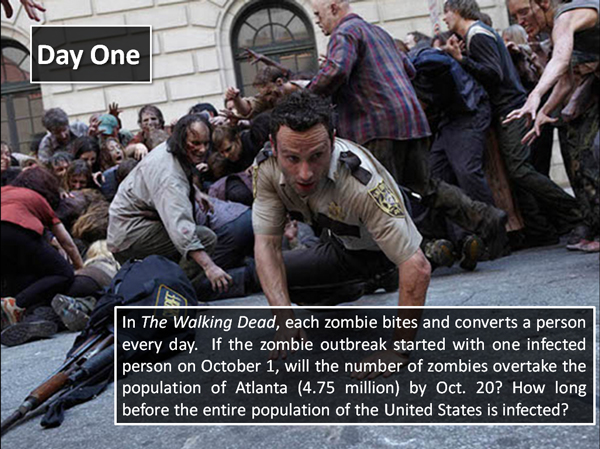

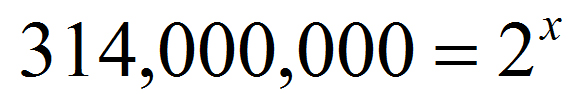

The Walking Dead is still a smash hit. Today, we got to solving logarithmic functions and we went back to that final question (which I purposefully left hanging back at the beginning) and solved it algebraically…

The Walking Dead is still a smash hit. Today, we got to solving logarithmic functions and we went back to that final question (which I purposefully left hanging back at the beginning) and solved it algebraically…

To say I had a desire to succeed with this lesson would be an understatement. I showed the Futurama clip to the parents and got all geeked up about how it would enlighten their children to the power of mathematics!!! In the end, it wasn’t the lesson that fell flat, but the sequencing of several lessons. That’s exactly why I’m blogging – so this gets recorded and I (perhaps some others as well) can make that enlightening lesson, you know, enlighten.

To say I had a desire to succeed with this lesson would be an understatement. I showed the Futurama clip to the parents and got all geeked up about how it would enlighten their children to the power of mathematics!!! In the end, it wasn’t the lesson that fell flat, but the sequencing of several lessons. That’s exactly why I’m blogging – so this gets recorded and I (perhaps some others as well) can make that enlightening lesson, you know, enlighten.

You must be logged in to post a comment.